Sickle Cell Disease: Nature’s Double-Edged Sword

CONTENTS

· Sickle Cell Disease (SCD)

· Prevalence of the condition

· Why does this harmful mutation persist in human populations?

· Mechanism

§ The Specific Mutation

§ How It Causes Sickle Cell Shape

§ Inheritance Pattern

§ Evolutionary Perspective

· Gene Therapies & Future Treatments – Era of Hope

· The Future: Awareness andAdvocacy

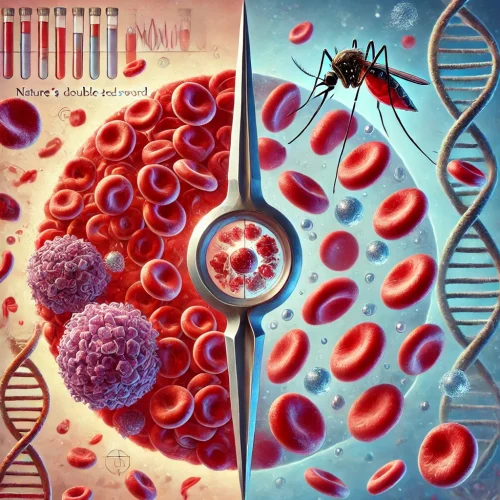

Let’s imagine genetic trait that protects you from a deadly disease but also brings immense suffering. This is the paradox of sickle cell disease (SCD), a condition shaped by both evolution and medical mystery. Sickle cell disease is caused by a mutation in the hemoglobin subunit beta chain (HBB), which affects hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. Normally, red blood cells are round and flexible, but in SCD, they become stiff and shaped like crescents or sickles. These misshapen cells get stuck in blood vessels, causing pain, organ damage, and life-threatening complications.

Prevalence of the condition

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is most common in populations with ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, India, and parts of the Mediterranean and the Americas. The high prevalence in these regions is due to the malaria resistance provided by the sickle cell trait (HbAS), which helped carriers survive in malaria-endemic areas. In India, sickle cell trait is found in 1%-40% of certain tribal populations, especially in central and western India.

Why does this harmful mutation persist in human populations?

The answer lies in malaria. Malaria is common in area, such as Africa, parts of the Middle East, and India. people with one copy of the sickle cell gene (carriers) have a survival advantage. Their red blood cells are less hospitable to the malaria parasite, meaning they are less likely to get severe malaria. This evolutionary trade-off is why the mutation continues to exist.

Mechanism

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is caused by a mutation in the HBB gene, which provides instructions for making beta-globin, a component of hemoglobin. This mutation leads to the production of abnormal hemoglobin S (HbS) instead of normal hemoglobin A (HbA).

The Specific Mutation

Sickle Cell Disease(SCD) is caused by a single point mutation in the HBB gene, which is located on chromosome 11. This gene provides instructions for making beta-globin, which is critical component of hemoglobin, the protein responsible for carrying oxygen in RBCs. The mutation occurs in the sixth codon of the HBB gene, where a single nucleotide replaces adenine(A) with thymine (T).This substitution alters the genetic code, causing amino acid glutamic acid to valine in the beta-globin protein. This small change has made significant effect on hemoglobins structure and function.

Sickle cell disease is caused by a mutation in the HBB gene, which leads to the production of an abnormal form of hemoglobin known as hemoglobin S (HbS). Under normal conditions, red blood cells are flexible and round, allowing them to flow smoothly through blood vessels. However, in individuals with sickle cell disease, hemoglobin S behaves differently, especially in low-oxygen environments. When oxygen levels drop, hemoglobin S molecules stick together inside the red blood cells. Instead of remaining separate and dissolved in the cell’s fluid, they form long, rigid strands that push against the cell membrane. This structural change forces the normally round red blood cells to distort into a crescent or sickle shape. Unlike healthy red blood cells, which can easily squeeze through tiny blood vessels, these sickle-shaped cells become stiff and sticky. They tend to cluster together, leading to blockages in small blood vessels.

As a result of these blockages, blood flow to various parts of the body is reduced or completely cut off. This deprivation of oxygen-rich blood causes severe pain episodes known as vaso-occlusive crises, which can damage tissues and organs over time. Additionally, sickle cells have a much shorter lifespan than normal red blood cells. While healthy red blood cells live for about 120 days, sickled cells break down within 10 to 20 days, leading to chronic anemia. The continuous shortage of red blood cells means that the body struggles to supply enough oxygen to tissues, contributing to fatigue, weakness, and other complications.

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, meaning that a person must inherit two copies of the mutated HBB gene one from each parent to develop the disease. If only one copy of the mutated gene is inherited, the person is considered a carrier but does not typically experience symptoms of the disease. Each individual has two copies of every gene, one inherited from the mother and one from the father. In the case of SCD, the mutation occurs in the HBB gene, located on chromosome 11. When both parents are carriers of the sickle cell trait (HbAS), there is a 25% chance with each pregnancy that their child will inherit two mutated genes (HbSS) and develop sickle cell disease. There is a 50% chance that the child will inherit only one copy of the mutated gene (HbAS) and become a carrier, and a 25% chance that the child will inherit two normal hemoglobin genes (HbAA) and be unaffected.

Individuals who inherit only one copy of the sickle cell gene, known as sickle cell trait (HbAS) carriers, usually do not experience symptoms of the disease. However, in extreme conditions such as high altitudes, dehydration, or intense physical exertion, they may have mild complications. Interestingly, carrying one copy of the sickle cell gene provides some protection against malaria, which explains why the mutation is more common in populations from regions where malaria has historically been widespread, such as Africa, India, and parts of the Middle East.

Evolutionary Perspective

Sickle cell disease is a prime example of natural selection in action, demonstrating how a genetic mutation can persist in populations due to its survival advantage. The mutation in the HBB gene, which leads to the production of sickle hemoglobin (HbS), is particularly common in regions where malaria has historically been a major cause of death.

Over time, the frequency of the sickle cell gene increased in malaria-endemic regions due to this selective advantage, a concept known as balanced polymorphism. In these populations, the HbAS genotype (carriers) became more prevalent because it conferred a survival benefit without causing the severe complications seen in individuals with two copies of the gene (HbSS, sickle cell disease).

The treatment landscape for sickle cell disease (SCD) is undergoing a revolutionary transformation, driven by advances in genetic therapies. While traditional treatments like hydroxyurea and blood transfusions help manage symptoms, they do not address the underlying genetic cause of the disease. Emerging therapies now focus on modifying or correcting the faulty gene responsible for sickle cell disease, offering the possibility of a long-term cure.

One of the most promising approaches is gene therapy, which aims to correct or compensate for the defective HBB gene responsible for producing abnormal hemoglobin. There are two main strategies in development. The first involves inserting a functional copy of the beta-globin gene into the patient’s stem cells to produce normal hemoglobin. The second strategy uses gene editing technologies, such as CRISPR-Cas9, to precisely modify the patient’s DNA, either by directly correcting the mutation in the HBB gene or by altering regulatory genes to increase the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF).

Another cutting-edge treatment involves BCL11A gene suppression. In early fetal development, humans produce fetal hemoglobin, which does not sickle and is highly effective at carrying oxygen. However, after birth, a gene called BCL11A suppresses fetal hemoglobin production, allowing adult hemoglobin to take over. Scientists have discovered that by turning off or reducing BCL11A activity, patients with sickle cell disease can start producing fetal hemoglobin again, which significantly reduces symptoms and complications. Clinical trials using this approach have shown promising results, with some patients experiencing reduced pain crises and improved overall health.

Bone marrow (stem cell) transplantation remains the only widely available cure for sickle cell disease today. This procedure replaces a patient’s diseased blood-forming stem cells with healthy stem cells from a matched donor, usually a sibling. However, due to the difficulty of finding a suitable donor and the risks associated with transplantation, including graft-versus-host disease, this option is not viable for most patients. Researchers are now exploring ways to use a patient’s own genetically modified stem cells to perform autologous transplants, reducing the risks of rejection. With these groundbreaking developments, the future of sickle cell treatment looks promising. Gene therapy and gene editing hold the potential to provide a one-time, lifelong cure for individuals suffering from the disease. While challenges such as accessibility, cost, and long-term safety need to be addressed, these advancements mark a turning point in the fight against sickle cell disease, offering hope to millions of patients worldwide.

The Future: Awareness and Advocacy

SCD primarily affects Black and African populations, yet it has historically received less attention and funding than other genetic diseases. Advocacy groups are working hard to change this by increasing awareness, pushing for better treatment options, and supporting affected families. As genetic research continues to evolve, we may soon see a world where sickle cell disease is not just treatable, but entirely curable. Until then, education, early diagnosis, and continued support remain crucial in improving the lives of those affected.